Isle of Misfortune

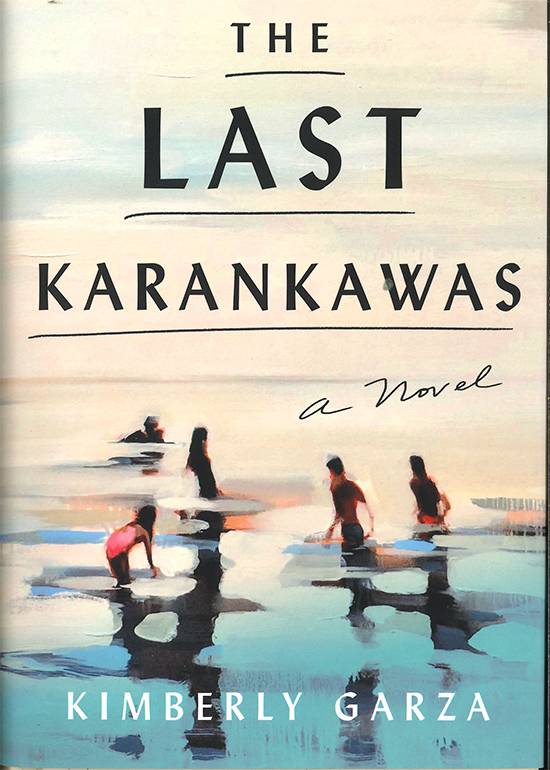

The Last Karankawas: A Novel

by Kimberly Garza

New York: Macmillan, 2022.

288 pp. $26.99 Hardcover.

Reviewed by

Danielle Muñiz

Kimberly Garza’s The Last Karankawas embraces Texas’s history with a whirlwind of narratives, characters, and conflicts that ache with trials and tribulations. Each page is wrought with her Filipinx, Chicanx, and Texan identity, rich enough to make audiences of the same communities warm with familiarity. The author’s writing is honest and clear distinguishing each character from one another and immersing readers into Texas’s different landscapes.

Garza’s imagery and descriptions of Texas environments and landmarks are recognizable to locals and informative for non-natives. She glorifies the coasts, relishes the mainland hills, dreams of the western deserts, and bathes in the salt water. Every landscape and natural phenomenon are written with such vigor that the reader is not simply observing a place but rather submerged in a feeling of intense aliveness. Garza relays this with a description of Hurricane Ike that is like a character of its own, “Ike has roiled and whirled, charged and swirled across the ocean…Draw near to Ike, who breathes them in and exhales them in pieces…Ike is cruelty and compassion both: tear down to raise up again in the image of what was and will be…” Through her characters and descriptions about the beauty or emotiveness of nature, the reader is left to consider the experience and meaning of their environment.

With thirteen different narratives to manage, Garza succeeds in establishing their own stories while still creating overarching themes. Each character has a challenging history: Carly abandoned by her parents at a young age, Mercedes crossing the border, Ofelia and Pierre assimilating for different people in different ways, and so on. However, constant ideas of freedom, running, and dreaming for something more is palpable, even in characters that do not have a point of view. Garza makes it clear that despite the similarities or differences they may share (whether age, gender, or culture), certain impulses or desires are simply human traits—whether considered ethically good or bad is to be said. Every character presented endures the human life of living with trial and error, making decisions and then dealing with the effects.

Carly, who renounced much of her Karankawa heritage and abuela’s stories, faces the decision of continuing her uneventful life with Jess and Magdalena or to drive down I-45 without looking back. As the novel starts partially with her backstory and point of view right after, her experiences and emotions lead the other narratives with themes of individuality, family, pain, and culture.

Garza makes jarring time jumps that are initially confusing about where we are in the lives of these characters but, once discussed further, can lead to understanding. The novel is not linear but skips forward years or throws readers into flashbacks, but the reader adapts due to Garza’s use of line breaks and growing use of obvious callbacks. The author also weaves each character’s story to share in the event of Hurricane Ike towards the end. By using this force of nature to tie in the timelines of the narrators as well as adding to the overwhelming emotions and thoughts they have, the connections between them and the setting fall in splendid harmony.

There is also the incorporation of first-person and third-person narration. The decision for only five chapters to be first-person inspires discussion of how it came to be as well as why these characters were given such control over their narrative for that one time. Carly, Magdalena, Maharlika, Mercedes, and the Queens of Santo Niño are first-person for one chapter at a time. Could their experiences hold more weight for the overall story and theme? Or their cultural connections? It seems to invite a thoughtful conversation even if it was an initial surprise.

Since the title of the book enticed me to pick it up, I wish there was more presence and discussion of the Karankawas to truly justify the name of the novel. More history and practices of Karankawas could have been incorporated by giving more chapters to Carly and her abuela, Magdalena, rather than Luz or Schaefer, whose chapters could pass as filler. Maybe by inputting more recognition and discussion of the Karankawas in more characters’ chapters, their presence would feel stronger. The name Karankawa given in the glossary at the end recovered some of what was missing, but more is encouraged to warrant the title of the book.

Despite the little hiccups, The Last Karankawas is an homage to Texas communities and life. It embraces all parts of identity including the internal turmoil that comes with being a human. Garza gives care to such themes through prose, dialogue, setting, and time. It is a mystical novel highlighting the beauty and storms of life.

Danielle Muñiz is a graduate student at Texas State University.