Critters

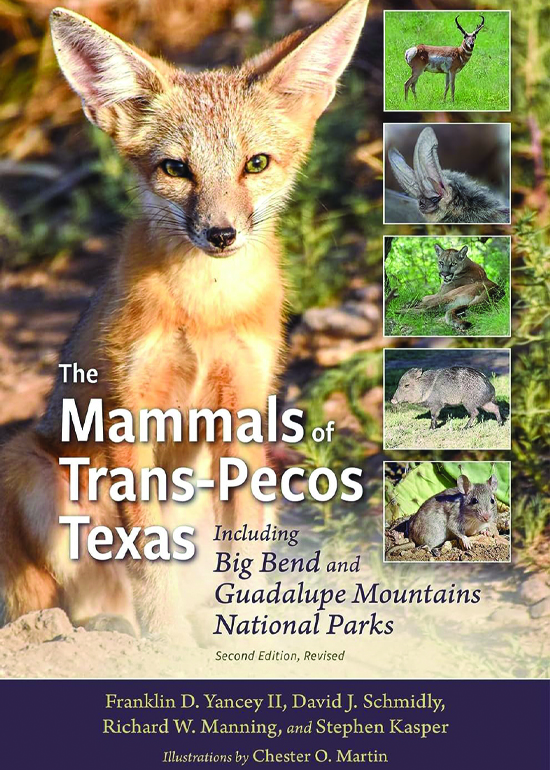

The Mammals of Trans-Pecos Texas: Including Big Bend and Guadalupe Mountains National Parks, Second Edition, Revised

by Franklin D. Yancey, David J. Schmidly, Stephen Kasper, and Richard W. Manning

College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2023.

488 pp. $60.00 Paperback.

Reviewed by

William Huggins

The Mammals of Trans-Pecos Texas: Including Big Bend and Guadalupe Mountains National Parks, Second Edition, Revised, introduces readers to mammals adjusted to aridity. The least-populated of Texas’s ten primary ecoregions, the Trans-Pecos “stands out as the most iconic, the most biologically diverse, and the most pristine.” In the initial 1977 volume, 102 published references occurred. This second edition includes almost 400 references and has been revised and updated to include new taxonomies, species, and technologies that made additional information possible.

The book opens with a description of the Trans-Pecos area. Maps throughout the book aid the text in providing place and context. Historically, the Trans-Pecos has seen significant changes in climate and biodiversity. The authors state that “simplicity has been [their] basic goal in organizing this book.” The opening chapter lists past and present climate, physiography, soils, and plant types, which well prepare the reader for the comprehensive listing of mammals that follows.

The longest section of the book, Chapter Six, packs an impressive amount of information and detail into each mammal. The Trans-Pecos contains 104 species of native mammals, over 70% of the 145 species of land mammals in the state of Texas. The chapter breaks down each family and species with information tailored to both the untutored and the professional. While every species does not gain representation in color photographs, most of the mammals receive a detailed pencil sketch which pairs each mammal with a map of its distribution in the Trans-Pecos, highlighting their rarity and ubiquity.

Chapter Six breaks down each mammal first by family, then by individual, complete with Linnean taxonomy and characteristic facts, including specific distinguishing traits, details of which emphasize: the specific habitat needs of the silky pocket mouse; the scarcity of the Trans-Pecos’s lone opossum; armadillos’ specialized carapaces; the wild assortment of the Trans-Pecos’s bats, the most diverse area of Texas for bats; new discoveries about gophers’ food-storage habits; and strategies of pocket mice and kangaroo rats for surviving extended periods of time without water by targeted foraging of appropriate seeds. The adaptations some of these mammals have made to survive arid conditions make for fascinating reading and highlight the new information that more than justifies the new edition.

The book also does not shy away from difficult history or current challenges. A section of the book focuses on extirpated mammals who once called the region home, such as the Gray Wolf, Grizzly or Brown Bear, and American bison, all hunted to extinction by human beings.

For those interested in the climate and biodiversity crises, Mammals of Trans-Pecos Texas offers a realistic assessment of these species’ possible future. Mammals of the Trans-Pecos face several threats, one cattle ranching, which led to “perhaps 30 to 40 percent of former grassland in the Trans-Pecos” now covered by desert scrub. Habitat disruption upsets delicate desert balances, affecting all wildlife in the area, and occurs from other introduced species such as feral hogs, burros, horses, and mules. Two species of the Trans-Pecos especially threatened are the stunning Pronghorn, the fastest land mammal native to North America, facing serious threats to traditional migration patterns from development as well as habitat loss; and American Beavers, who in an era of diminishing water yields have taken to building burrows instead of dams, adapting to their arid reality.

The book’s final chapter lays out not only criticisms but possible conservation solutions for “saving the last frontier.” For those who love arid areas and the nonhuman kin with which we share them, this may be the most important section of the book. The book was published before Exxon-Mobil’s decision to purchase Pioneer Natural Resources for $59.5 billion, expanding their reach into the Permian Basin. Yet Mammals of Trans-Pecos Texas could be accused of foresight: “the Trans-Pecos borders one of the most productive energy areas in the world, the Permian Basin, the geographic footprint of the energy industry has slowly surged its way into the region.” The book also notes that “climate change has become a serious threat entering the twenty-first century, and Texas is one of the states predicted to experience the worst of this problem.” Yet we still have time, as the authors implore us in the book’s final paragraph, “to work together to ensure that the encompassing wilderness area that we call the Trans-Pecos, with its spectacular vistas and natural and cultural history, is preserved and protected for the future.” The book offers solutions for us as well as the Trans-Pecos wildlife, if we are wise enough to heed them.

William Huggins is a writer and eco-critic who lives, writes, and works in Las Vegas. His fiction and criticism have appeared in multiple venues.