Don’t Bring Your Guns to Town

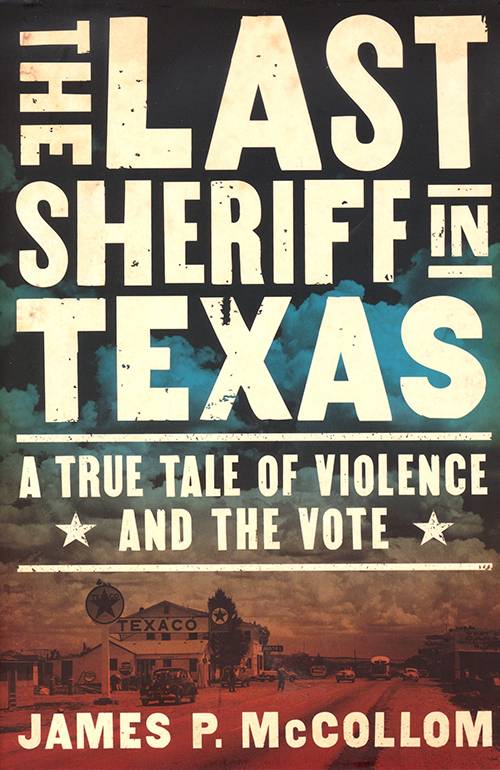

The Last Sheriff of Texas, a True Tale of Violence and the Vote

by James P. McCollom

Berkeley: Counterpoint, 2017.

257 pp. $26.00. cloth.

Reviewed by

Joe McDade

There is an old Texas saying: Every little town has somebody.

In Beeville, Texas, in the years following World War II, that somebody was—is, to this day—Vail Ennis, a sheriff of such authority and valor that, as so often happened, he turned into a law unto himself. Ennis became a hero in 1947, when he handcuffed two prisoners together but didn’t know one was carrying a Smith & Wesson .38. When Ennis turned his back to make a phone call, the prisoner drew the gun and shot Ennis five times in the belly. Astonishingly, Ennis managed to draw his revolver, empty it, reload, and empty it again. Ennis survived; the two prisoners did not.

The incident made Ennis a national hero, the focus of a Time magazine profile, and an instant legend alongside such Texas lawmen as Frank Hamer and Alfred Allee. The problem was, as James P. McCollum writes in his superb book, The Last Sheriff in Texas: A True Tale of Violence and the Vote, that Ennis’s fame gave him an exalted sense of himself and his authority. In a tale as old as Texas itself, Ennis’s belief in his omnipotence became his undoing.

Ennis was a sheriff who often ignored the rule of law, even if he was often on the side of the angels. A distraught mother might come to Ennis and complain that her spouse was drinking up his paycheck; Ennis would simply stride into the corner bar and shake down the sloppy husband for whatever money remained. In one notable incident he came across a man bothering a local waitress and, when his powers of persuasion came to naught, beat the man senseless. What these incidents have in common was Ennis’s laudable (if overreaching) tendency to side with the powerless against the forces of menace. In the end, however, it was Ennis’s status as a law incarnate that made him the menace.

Whatever else Ennis was, he wasn’t a racist, at least by the standards of the time. His treatment of Beeville’s substantial Latino population was, for better or worse, about the same as his treatment of Anglos. However, it was his killing of the Rodriguez brothers that served as the tipping point for a coalition of Beeville citizens to remove the sheriff once and for all. McCollom writes, “In a shootout west of town, Vail had shot down the three Rodriguez brothers—Felix, Domingo, and Antonio, all highly respected farmers. Some people said it was a shooting, not a shootout. They said the Rodriguez boys hadn’t fired a gun.”

Enter Johnny Barnhart, who had been born and raised in Beeville, attended the University of Texas, and had been elected to the State Legislature. Had Barnhart never taken on Ennis, Barnhart would still own a sliver of Texas history as the only legislator not to vote for the vile Texas Anti-Communist Control Act, a law that would require all Communists to register with the State Department of Public Safety. Barnhart, recognizing the bill’s clear violation of the Constitution’s right to assembly, attempted to return the legislation to committee, hoping it might die there; failing that, in the up-or-down vote on the act, Barnhart voted present, the only one of 137 legislatures not to vote yes.

Barnhart returned to Beeville, took up a law practice, and plunged himself into what he saw as Ennis’s tyrannical and hanging-judge mentality. In time, he found himself leading a small but dedicated crusade against Ennis, which culminated in Barnhart’s Citizens for Good Government, a group that led three factions: the avatars of the New South, the citizens pining for the rule of law, and Latinos still burning over the Rodriguez killings. The effort to oust Ennis culminated in the 1952 sheriff’s election.

The candidate that Barnhart’s group backed was the humble, soft-spoken Louie Duffy, a lawman utterly devoid of charisma and a talent for public speaking. At a candidates’ forum, following a rousing Vail Ennis stemwinder, Duffy gave his speech, the entirety of which is as follows: “’My name is Louie Duffy. I will appreciate if you will go to the polls July 26 and vote for Louie Duffy for sheriff. I thank you.’”

As it turned out, Duffy could have read from the Beeville phone directory, for all that it mattered. The election was a plebiscite on Ennis, plain and simple.

From the beginning Barnhart had attempted to keep the election away from simplistic reductions: polished Austin legislator versus small-town sheriff, city versus country, college versus street-smart. He specifically—some said obsessively—downplayed the Latino element of his Citizens for Good Government, making sure the election was not cast as Latino versus Anglo. To Barnhart, the election was about suspects not being unjustly beaten, suspects receiving proper bail, suspects receiving a trial before a judge and jury. Vail Ennis had kept the peace, as he had seen fit, but times had changed, and Ennis had refused to change with them. To the surprise of no one, Duffy won the election by 200 votes out of 4,300 cast. Ennis was out. Even so, he remained—remains—a Beeville legend.

Every little town has somebody.

Joe McDade is a professor of composition and American Literature of English at Houston Community College. He also lectures on English Composition at the University of Houston.