The Great Wings Beating Still

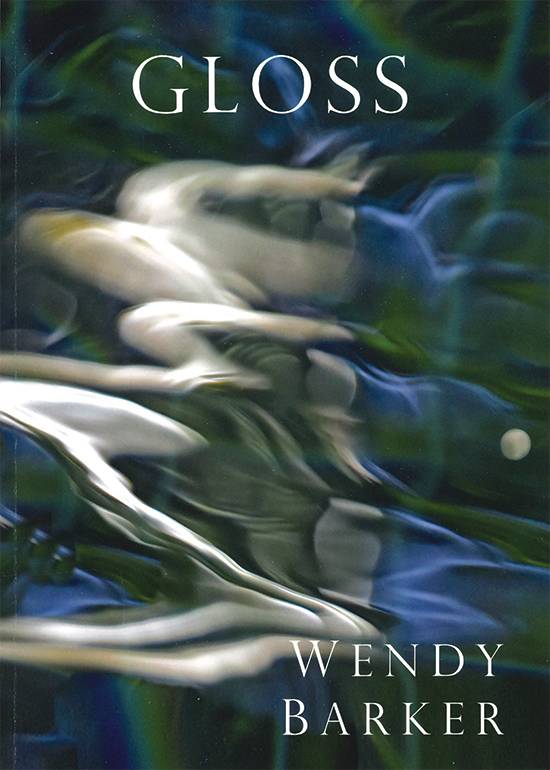

Gloss

by Wendy Barker.

Houston: Saint Julian Press, 2020.

71 pp. $16.00 paperback.

Reviewed by

Anthony Isaac Bradley

Wendy Barker’s new poetry collection, Gloss, offers the narrative of a mother-daughter relationship and how family history—and birthplace—inform success and failure. Organized by what appears to be infinity symbols (though the font makes me question this interpretation) Barker explores present and past echoes, “from one life to another” as the family graduates from one location to the next. As the speaker’s mother hails from the UK, one senses that these echoes exist because loved ones are never in the same space for too long. Once they stop moving, it’s all over.

Despite the state/country hopping, Barker’s Southern identity travels throughout this collection alongside her mother’s British social and emotional influences. “Sunday Lunch at Mom’s Cousin Dinnie’s: June 1969” deals in the dialect of her mother’s people, juxtaposed against the sounds of everyone she encountered (“‘Sheee-it, Man’”). The daughter struggles to keep up as she relocates throughout her life. “I know I drag out my vowels, multiplying dipthongs / into tripthongs” she says, reflecting on a friend who found her accent “soothing.” She states later: “My / mother would have been horrified.”

“Incest,” is a brief but lingering comment on family lore and British royalty tradition. Managing to be both funny and tragic in such a tiny space is impressive. I found myself thinking about this poem long after I read it. The poem’s final line, “There were no horses,” ties into King Edward VII’s quote from the front pages which states, “I don’t very much care what people do as long as they don’t do it in the street and frighten the horses.” This poem keeps its shame and sexual history beneath the surface but the conversation underneath is easy to hear. Admittedly, with such a blank or deadpan tone, reader reactions to “Incest” may vary. That said the poem makes an impression that’s difficult to ignore.

Gloss places its speakers on a map, then plucks them over to a new location. “Accounting for Granny” traces the title person as she relocates from Wales, to China, to India. After traveling the world, Granny finishes her existence in a more intimate location: “And how did it happen that, after Grandfather died, it was Granny all by / herself in a ratty hotel before she rented her flat, a one-bedroom ‘efficiency.’” Their family history is one of illusion. There is no romance in death, no matter how many storied cities are checked off along the way. Reality is a studio apartment, not the Eiffel Tower.

Speaking of France, the book’s closing poem, “Beyond A Certain Age, I Look for Paris in Paris,” brings family members in for their personal thoughts on Paris, some less than favorable. “Maybe I have actually become my British / uncle. Samuel Johnson said if you’re tired / of London, you’re tired / of life.” By the poem’s end she accepts the reality of this place that she and her family frequented, despite the differences: “[Visible] muck, and tiny speckled fish burbling to the surface, then / spiraling back down to the silt, murky depths, / the dirt that underlies us all.”

In “Surgery, A Little History,” the body is seen through a medical lens. There’s a moment where the speaker is used as an anatomy example for nursing students, all who ignore any semblance of dignity in lieu of “hooting” as she is stripped. Baker begins the poem with a mention of Yeats to set up the above: “Stunned by the god’s ‘feathered glory,’ Yeats wrote / of Leda, in one of my mother’s favorite poems. How many / painters have rendered this image, of a woman swooning.” The author continues this avian diction that comes packaged with its many connotations: freedom, survival instincts, and the sharpness of a parent’s mouth (beak). Baker manages to avoid cliché territory despite this reliance on bird imagery. “Surgery, A Little History” brings to mind the poem “It Was My First Nursing Job” by Belle Waring, where medical malpractice is used to discuss how violence takes form in adult-adult and adult-child relationships. This poem continues Barker’s attention towards family secrets as the speaker’s mother recounts an assault by her gynecologist. The violence in this moment appears less visceral than in Waring’s poem, which allows the mother and daughter’s personalities to express the vulnerability of the unfamiliar, a sentiment that Gloss ultimately wants to capture: “‘we’re going / to a hospital, honey, just a little operation.’”

Anthony Isaac Bradley’s writing has appeared in Prairie Schooner, Coachella Review, Cimarron Review, and other lovely places. He’s a two-time Pushcart Prize nominee. He lives with his cat and the ghost of another.