It's What's Inside That Matters

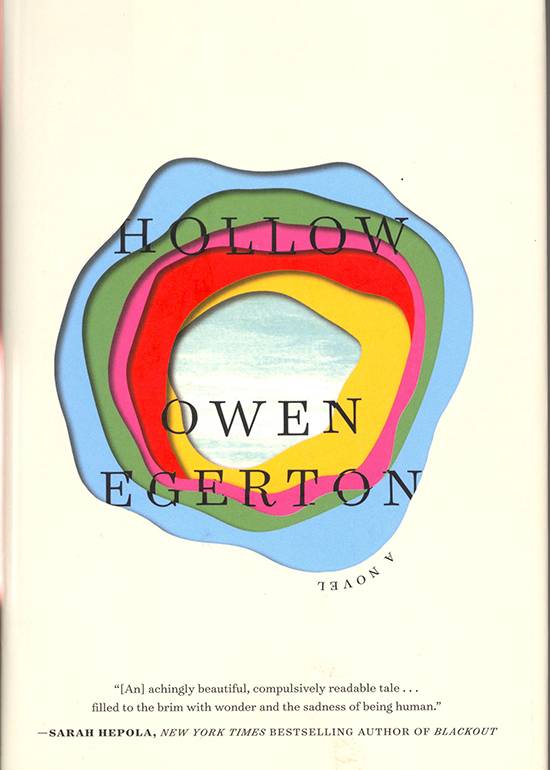

Hollow

By Owen Egerton

New York: Soft Skull Press, 2017.

237 pp. $26.00 cloth.

Reviewed by

William Jensen

The newest novel by Owen Egerton, Hollow, is a meditation on grief disguised as a comedic romp. The book’s protagonist, Oliver Bonds, used to be a bright and upcoming professor of religious studies, but he is now a derelict living in a shack and roaming the streets and back alleys of Austin, Texas. There are echoes of other down-and-out narratives ranging from McCarthy’s Suttree to the more sentimental stories of Charles Bukowski. Bonds may be down, but he’s not out for the count quite yet. The novel begins with him finding a new inspiration in a community of other misfits who believe that the world is hollow.

There are, essentially, two narratives in Hollow. One details the current adventure of Bonds and his friends who follow the writings of “scholar” Dr. Jim Horner and his theories of how Earth is hollow. The other is the history of Bonds’s fall from grace. Egerton balances both arcs carefully and artistically. As one plot moves forward, it becomes enhanced by the reflective backstory, and it is not just simple exposition—the storylines ultimately become dependent on each other and build toward a crescendo.

The novel focuses primarily on Bonds’s escapades with fellow oddballs, rebels, loners, and losers—there is Lyle who is a conspiracy theorist, Martin who has had cancer for so long that he was kicked out of hospice, and there is Laika who is a prostitute with a suspicious Russian accent—but the real heart of Hollow is in Bonds’s tragedy: the death of his infant son, Miles. In the hands of a lesser writer, a story of a losing a child would come off as maudlin, but Egerton keeps the writing tight and reflective in the best way. You believe Bonds when he says, “After Miles died I stopped reading. I purchased books, opening them, turned their pages. I still fell asleep with an open book on my chest nearly every night. But I never read a word past the title, and often not even that.” As Oliver Bonds goes further into the madness of finding the hollowness of the world, he delves deeper into his own grief and may just end up pulling himself out alive through the other side.

Egerton intelligently keeps everything dealing with bereavement as an undertone rather than a full-on assault. As Bonds meanders through Austin and the outskirts of the capitol city, he hopes to catch a bit of redemption or maybe just an ounce of forgiveness. He wants to believe there is an Eden at the core of the empty planet, but deep down he knows he is only trying to mask his pain. In this way, Egerton is a dark satirist with hints of Kurt Vonnegut and Harry Crews. The reader is never sure if Bonds is actually going to make a trip to the North Pole (where the best entrance to the empty center awaits) or if he will regenerate into something of his old self. This suspense is where a lot of the fun is. Egerton manages to keep things dangerous without losing control or seeming reckless.

Ultimately, Bonds and his search for meaning becomes a deeper quest than maybe even he realizes. He tries to help his friends, he tries to do the right thing, but he eventually concludes that “our lives are crust until something cracks them open… Then you can look inside.” You’ll find yourself rooting for Oliver Bonds not because he is always likeable but because he is an Everyman on a quest that is unusual, intriguing, relatable, and sad. The past and the present become inseparable just as thought must be influenced by memory. The scenes between Bonds and his ex-wife are especially difficult to read because they seem too true, too honest. But these scenes work because there are also plenty of humorous moments involving the Hollow Earthers and their meetings at the local YMCA.

Egerton’s writing is consistently natural and fluid. At times you may even feel as if you’re falling into the pages, forgetting that you’re reading fiction. There isn’t a single line that is awkward or clumsy. However his descriptions of Austin are slightly vague, and at times the book feels as if it could be set anywhere. There are a few mentions of Zilker park and grackles, but Egerton’s sense of place is the book’s weakest element. Of course, Hollow is not trying to be the great Austin novel—but it is easily the best book of the year set in the city of the violet crown.

William Jensen is the editor of Southwestern American Literature and Texas Books in Review. He is the author of the novel Cities of Men.