The Greatest Generation

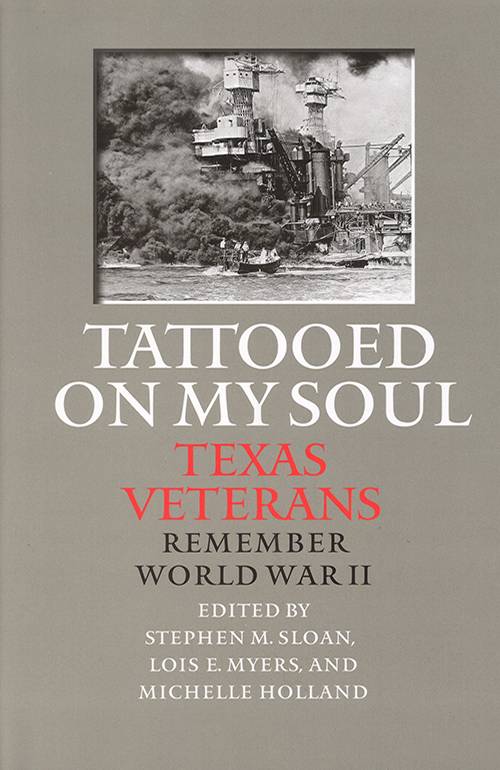

Tattooed On My Soul: Texas Veterans Remember World War II

Edited by Stephen M. Sloan, Lois E. Myers, and Michelle Holland

College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2015.

283 pp. $29.95 cloth.

Reviewed by

Dan Utley

With the sustained evolution of professional oral history methodology since the mid-twentieth century has come a greater appreciation for the scholarly value of the military memoir. Once largely relegated to the verification of tactics and strategies or to the documentation of unit histories, first-person accounts of military service now serve as viable venues from which to explore related contexts of societies, cultures, communities, and families during wartime. Military conflict provides an ideal expansive canvas for such explorations of great change over relatively short periods of time, and oral histories deliver shared relevance through the lives of individual service personnel. All eras of conflict, though, are subject to limitations of the time continuum, and the viability of collected stories is proportional to select elements of the bigger picture. In the case of the U.S. involvement in World War II, for example, the government leaders are gone, as are the flag commanders, and the remaining available stories are now largely those of the rank and file. As historians are acutely aware, the available pool for firsthand accounts of World War II is rapidly diminishing and in a few short years will no longer be accessible. At some point, the stories will shift to the home front and then to the children of the war, and then even those aspects will disappear.

Given the depletion of historical resources, works like Tattooed on My Soul take on even greater significance. That is especially true in this case, because the editors have done an outstanding job of developing accessible narratives from the more clinical recordings and verbatim transcripts, both of which have their own inherent limitations. As Stephen M. Sloan, Lois E. Myers, and Michelle Holland note, “We editors want to stand aside and be forgotten while the reader meets the narrator. We therefore impose ourselves sparingly.” Editing the transcripts to take out the questions, prompts, and interjections of the interviewer, while preserving the scope, intent, and vernacular rhythms of the interviewee is difficult, but it makes for compelling reading. Thanks to that process, one begins to understand with enhanced clarity the extraordinary lives of ordinary people in times of war. The memories are not just for those interested in military history and the role Texans played in the war, however, but for those who appreciate how individual change fuels societal change as well. In that regard, Tattooed on My Soul is a worthy heir to such landmark works as Studs Turkel’s The Good War (1984) and Tom Brokaw’s The Greatest Generation (1998).

The scholarly value of the book is bolstered by the manner in which the editors—colleagues at the Baylor University Institute for Oral History—provide meaningful construction. The text is inclusive, broad-based, and in large part chronological, with key divisions entitled “There at the Start: 1941-1942,” “There in the Thick of It: 1943-1944,” and “There at the End: 1944-1945.” Within each division then are the focused, first-person accounts of “The Witnesses.” Each individual memoir begins with an abstract of the interviewee’s personal background and ends with a brief epilogue that brings the story to the present. In between is the literature of the remembered past told by those who lived it.

The voices of the war include a pilot in Doolittle’s 1942 raid on Tokyo, a member of the Women’s Army Corps, liberators of Paris and the concentration camp at Nordhausen, foot soldiers who stormed Omaha Beach, a prisoner of war, front line doctors and nurses, college students in military training, and those who celebrated key days of victory overseas. The witnesses tell their stories through personal lenses of memory and the spoken vernacular of their own sense of history, and the results are powerful, poignant, and compelling. These are the historical records of emotions and personal challenges, and of how, as the editors noted, “the events of World War II were made manifest in the living of a life.” In the leadoff account, Frank Curre, Jr. remembered:

“You know, the war is tattooed on your soul. You’re never going to forget it. You might forget small details and dates. But the one thing that I liked that we ain’t got now: the whole nation was one family. Part of the family had to go to war and fight the war and win the war. The rest of it stayed here: made, produced, melted, made all the sacrifices, had all the victory gardens, and built what it took for us to win the war.”

It is important to note, too, that the family analogy extends well beyond to those who help preserve such wartime memories as well, and includes oral historians, researchers, transcribers, editors, fact checkers, archivists, family members, and many others. As this book clearly illustrates, the accounts it conveys are only a small part of a much larger story, but given the continuum of time and the lack of similar studies, the value to our collective memory can only increase.

Dan K. Utley is the Chief Historian with the Center for Texas Public History at Texas State University. Oral history interviews he conducted in the early 1990s with World War II seaman Edward F. Wegner of Burton, Texas are included in the book he reviewed.