Pretty As A Picture

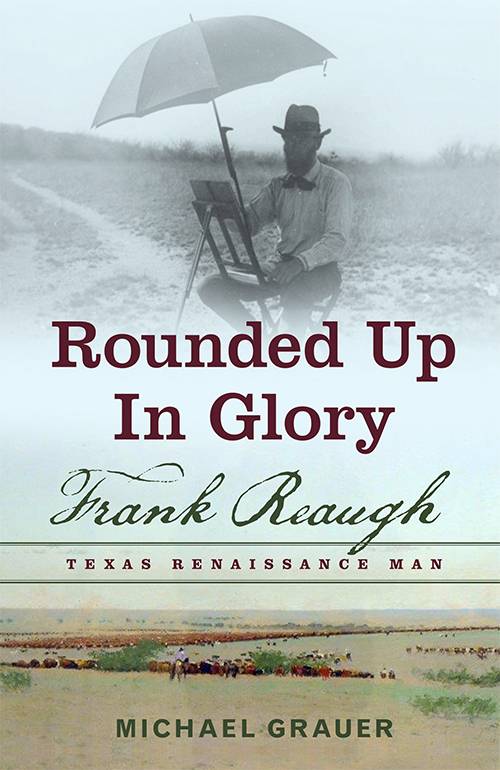

Rounded Up in Glory: Frank Reaugh, Texas Renaissance Man

by Michael Grauer

Denton: University of North Texas Press, 2016.

480pp. $39.95 cloth.

Reviewed by

Light Townsend Cummins

Longhorn cattle rank squarely among the most iconic and recognizable symbols of the Lone Star State. With the possible exception of the Alamo, an encircled tin star, or a field of bluebonnets, no symbol evokes Texas in the mind of people across the globe than the distinctive horns of a longhorn cow. As well, the fabled era of the open range cattle kingdom during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries has consistently provided fertile ground for codifying the myth and memory of Texas as a unique place in the history of the American frontier. Given the exalted role the Longhorn cow and the cattle ranges of the state have played in defining our history, it is absolutely remarkable that one of the greatest artists of that time, Frank Reaugh (pronounced Ray) who painted and sketched thousands and thousands of images of open range Longhorns, has remained mostly unknown to the general public. Reaugh lived from 1860 until 1945, spending most of his life as an artist based in Dallas although he travelled extensively throughout the cattle areas of the state. A professionally trained painter and watercolorist who studied in France as a young man, Reaugh’s work constitutes some of the best examples of impression ever seen in the Southwest. Nonetheless, his name is usually recognized only among those familiar with the history of the arts in Texas. Sometimes called in art history circles the “Painter to the Longhorns” or the “Dean of Texas Painters,” this important artist has never been the subject of a complete, scholarly biography. And, to date, the few general publications about him written over the years have never attempted to set the full story of his life into the framework of this state’s cultural history.

All of that definitively changes with the publication of Michael Grauer’s Rounded Up in Glory: Frank Reaugh, Texas Renaissance Man. This important new volume has been a lifetime in the making when one considers the time and effort the author has expended in bringing this significant book to the reading public. Grauer, who is a professional art historian, has been Curator of Art at the Panhandle Plains Historical Museum for over a generation. This museum holds the largest collection of works by Reaugh, along with the archival personal papers of the artist. Grauer has thus lived with Frank Reaugh and the artist’s legacy every day for over a quarter century while he studied Reaugh’s correspondence, assessed his art, and considered the impact of this art on the development of the state’s culture and identity. In making this observation, however, it must be stressed Michael Grauer is not a “one trick pony” whose single expertise is this particular artist only, although he is most certainly the reigning Reaugh expert by any measure of accounting. Over the decades, Grauer has risen to the first rank of art historians in the Southwest, publishing an impressive array of books, essays, and art catalogs dealing with a variety of subjects including women in the arts, western art, and the importance of impressionism in Texas art history. In spite of this impressive record of diverse publication, however, Frank Reaugh has never been far removed from Michael Grauer’s awareness in his capacity as a well-known commentator about the art of this region. That expertise is manifested on every page of this book, while it permits the author to place Reaugh within the fullest possible historical context.

Frank Reaugh’s life was as colorful and distinctive as the art he produced. Born in Illinois, Reaugh moved as a child with his family to Terrell, Texas, where he grew up. He began sketching from an early age, often drawing the livestock that surrounded him during his formative years. As a young man in his twenties, he studied at the St. Louis School of Fine Art and at the Académie Julian in Paris, France. He moved with his family to Dallas in 1890, where he lived until his passing.

Reaugh soon began travelling across Texas, especially the western regions of the state, where he paid particular attention to drawing cattle on the open range. He also taught art lessons to students in Dallas, combining his instruction of them with sketching trips across the Lone Star State. By the turn of the twentieth century, Reaugh annually led a summer-time trip for his students during which they variously visited locations including the Panhandle, down through the Caprock or the Brazos Breaks to the high country of the Callahan Plateau toward the Chihuahuan desert lands, and across the Trans-Pecos into stretches of far West Texas. The art produced on these trips constitutes an invaluable chronicle of the natural beauty of Texas during a time it was still pristine and also of the cattle kingdom during the period of its greatest historical significance.

Reaugh was also a tinkerer, an inventor of sorts, holding several patents on engine design, a rotary pump, and a portable sketching chair for out-of-doors use. He made his own pastel chalk and other of his art supplies. He was also civically active as a founder of the Dallas Public Library and the Dallas Art Association. By the late 1920s, however, Reaugh’s considerable artistic standing in Dallas and across the state had diminished with the rise of modernism as embodied in the American Scene movement and with the growing centrality of Texas Regionalism. Younger artists of that era, especially the Dallas Nine and other Regionalists, depreciated Reaugh during the Great Depression and criticized him as being out of step. They dismissed Reaugh as old fashioned and artistically inconsequential in the face of modern times because he continued to embrace impressionism, an artistic style they dismissed as passé. His final decades were sadly for him a time of progressive isolation as he became increasingly unappreciated in spite of his considerable contributions to Texas art and its development.

Today, happily, Frank Reaugh’s star is rising again three generations after his death. Several museums in the state have recently sponsored major exhibitions of his work while a documentary filmmaker has turned to telling his story. Michael Grauer’s biography of him will accelerate this growing appreciation of Reaugh and his contributions to Texas art. In that regard, it should be noted this volume is biographical writing at its best. It is based on impeccable archival research while it relates Reaugh to the art of his times. However, it is not a dry art history designed to appeal only to specialists—this is a carefully crafted biography that brings its subject to life. It is certain this book will occupy an important place any future bibliography of Texas history that seeks to be comprehensive. Importantly, Michael Grauer’s biographical study will undoubtedly insure future generations of Texans will know Frank Reaugh and understand the singular role this artist played in the cultural history of Texas.

Light Townsend Cummins is the Bryan Professor of History at Austin College and a former State Historian of Texas. He writes from the viewpoint of a historian interested in the cultural aspects of Texas art and artists. Among his recent books are Discovering Texas History, Allie Victoria Tennant and the Visual Arts in Dallas and Texan Identities: Getting Beyond Myth, Memory, and Fallacy in Texas History.