Love Games

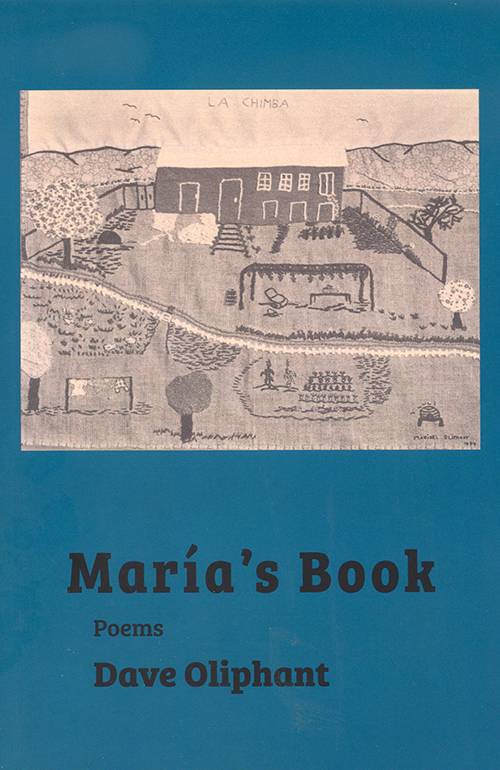

Maria's Book: Poems

by Dave Oliphant

Seadrift: Alamo Bay Press, 2016.

150 pp. $15.95 paper.

Reviewed by

Zach Groesbeck

The only thing possibly older than poetry is love. And the oldest gesture in poetry is love. While the canon is overflowing with enamored and erotic voices, the modern love poem has diminished in popularity. For love poems to be successful in contemporary literature, they have to be familiar to their audience, but simultaneously new and refreshing to the genre. One poet who is able to achieve the delicate craft of writing beautiful love poems is Dave Oliphant.

Many of you are probably familiar with Oliphant. Through a roughly forty-year career of publishing poems, translations, biographies, editing anthologies, and teaching at the University of Texas in Austin, Oliphant has cemented himself as one of the state’s leading writers. Oliphant’s newest collection María’s Book, a project that took forty-one years to finish, commemorates his golden wedding anniversary to his wife, María.

The considerable time span of the collection’s composition (coupled with the construction of the book) sets it apart from anything else in contemporary verse. Beware MFAers, these are not workshop poems. Yet, this heed isn’t as preface for a negative review, in fact, the contrary is true. Oliphant’s style—favoring a less polished, but more authentic voice—is what’s most exciting about his work.

Each of the collection’s fifty-five poems are titled as something María possesses, such as “María’s Antiques,” “María’s Dresses,” or “María’s Wool.” Readers will notice Oliphant’s disinterest with a sequential organization as the poems are arranged alphabetically, instead of narratively or associatively, rendering the book encyclopedic. Rather than conveying María through story, Oliphant conveys her through her embodiment across a wider catalog of her belongings and her actions. While Oliphant meditates on numerous expected subjects, such as “María’s Smile” and “María’s Heart,” he also routinely delivers surprises, finding beauty in the mundane of “María’s Lamp” and “María’s Sewing Machine.”

In “María’s Miracles,” Oliphant observes in an ordinary interaction between María and the family cat, something that, because of his intense emotional enthrallment, he finds miraculous,

she performs them day & night

as when she gives the cat a kiss

on its furry blue-point face

then lets it stretch & softly knead

with paws against her Chilean cheek

when husband & kids hoot & hiss

yet believe in such a miraculous sight

permitted even the unworthy witness

The risks any writer takes in writing love poetry is alienating the reader by failing to create place where a third party spectator can enter into the two-person relationship. Oliphant compensates for this by frequently using common events as subject matter, taking advantage of his readership’s familiarity with similar experiences. His juxtaposition of miracle with the mundanity of the event is understatement, acknowledging his subjective embellishment, producing the necessary space for readers to enter objectively into Oliphant’s enamored subjectivity.

While Oliphant also sacrifices incisive image-making and economical language, he in turn gains an elation in tone. In “María’s Readings,” Oliphant depicts a mutual love for literature through familiar acts of reading before bed and sharing new or obscure authors with each another—subjects not usually found in poetry—managing to make these routine activities serve as evocative instruments of romantic fervor,

just such delicate things on earth

subjects of her secondhand books

friends she lives with on intimate

terms caressing not caring if she

bends their backs even wets them

in her bath as juice from orange

apple or pear runs down her chin

the unread poet can’t wait to kiss

Oliphant’s formal decisions are pronounced and distinctive. His line breaks on prepositions and his minimalist syntax, reminiscent of both Robert Creeley and William Carlos Williams, along with the unpunctuated sentences together invite multiple readings of the poems, enhancing their ambiguity—their range of possibility, not vagueness—by blending sentence endings and beginnings, creating a multitude of other possible sentences and meanings. Oliphant also has an affinity for rhyme and musical meter, which are mostly absent from contemporary poetry. So while he’s not a neo-formalist seeking to reinvent the sonnet, his use of such techniques, which he largely accomplishes in subtly, cater well to his plainer diction and the sometimes end-stopped lines.

While none of the poems in María’s Book are in apostrophe—speaking directly to María—they are brimming with Oliphant’s unwavering passion. Much of the content likely carries more emotional weight between Oliphant and his wife than Oliphant and his reader. Yet this isn’t a failure of the book, it’s where it succeeds most. Much of what makes two people fall in love happens in the spaces between cherished memories. Oliphant, recognizing this, celebrates love in every moment, from the most incredible to the most typical.

Zach Groesbeck is a graduate student in the MFA program at Texas State University.