Shoot ’em Up

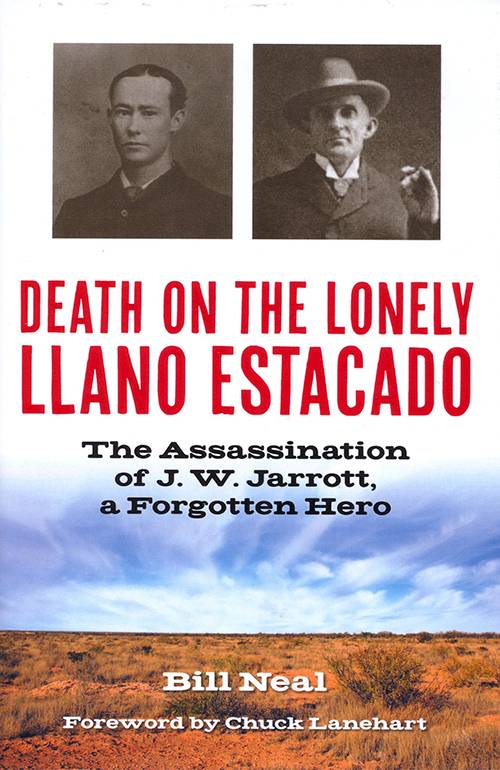

Death on the Lonely Llano Estacado: The Assassination of J.W. Jarrott, a Forgotten Hero

by Bill Neal

Denton: University of North Texas Press, 2017.

240 pp. $24.95 cloth.

Reviewed by

Joseph Fox

On August 27, 1902, an unknown gunman assassinated politician J.W. “Jim” Jarrott at the Twin Mills Lake, which is just outside Lubbock. In Death on the Lonely Llano Estacado: The Assassination of J.W. Jarrott, a Forgotten Hero, historical author Bill Neal, ties Jarrott’s assassination to the conflict on the South Plains of the Llano Estacado between the ranchers and incoming homesteaders (or ‘nesters’) over a portion of 2,560 acres of public land commonly referred to as ‘The Strip.’ With both a lawyer-like ability to gather evidence and a writer’s ability to craft an engaging story, Neal presents a persuasive argument that the culprit behind the Jarrott assassination was the professional killer “Deacon” Jim Miller and his business partner who was also the owner of the near-by Lake Tomb Ranch, Marion Virgil “Pap” Brownfield.

Having written other books about murder on the Texas frontier, Neal is the perfect writer to tell this story. Beginning in the winter of 1901, the reader is planted with Jarrott, his wife, Mollie, and the twenty-five homesteader families he brought by wagon to the Strip, which was made available through a deal between Jarrott and the Texas General Land Office. While homesteaders and farmers on the Texas Panhandle are often overlooked, Neal argues that the homesteaders, enabled by the 1895 Four-Sections Act, are the people who deserve the most credit in opening up the Llano Estacado in North Texas for settlement. While Texas is not the only frontier state to have homesteaders, Neal points out that Texas is the only state to retain control of its public land and therefore have its own homestead laws. With farmers moving to the South Plains, the local ranchers feared Jarrott would open the area for other families to move in and consume the already scarce quantities of land and water.

After trying various methods (both through legal and physical intimidation) of driving the homesteaders from The Strip, Neal argues that Pap Brownfield hired hitman “Deacon” Jim Miller (who was already a business associate) to assassinate Jarrott under the assumption that the other homesteaders would flee without their leader. Miller, who earned his nickname through his ability to befriend and blend with the respectful elements and religious congregations of frontier towns, was by Neal’s analysis a master of murder for profit, and using a variety of tactics to get acquitted. Even though Miller (and his employer Brownfield) got away with Jarrott’s murder at the time, Neal connects the dots by way of his financial dealings with Brownfield and a later confession from Miller to lawman Jack “Catch ’em Alive” Abernathy (who as fate would have it later married the widowed Mollie Jarrott). While Miller eventually found justice by way of a lynch mob for a separate murder, his employer Brownfield became the namesake of the nearby town of Brownfield in present day Terry County. In light of this grisly history, Neal quotes South Plains historian Chuck Lanehart in posing this question to the reader: “Shouldn’t the South Plains city of Brownfield be renamed ‘Jarrottville’”?

While Neal crafts an airtight argument linking Brownfield and Miller to the Jarrott murder, his depiction of Panhandle ranchers at times leads them to come across monolithically as ruthless villains who stood as a class against the homesteader encroachment in the South Plains. Readers would be well served to supplement this book by reading classics on Panhandle ranchers such as J. Everett Haley’s books Charles Goodnight: Cowman and Plainsman and the XIT Ranch of Texas. In these classic works, Haley argues that, contrary to popular perception, ranchers (and railroads) played a major role in encouraging farmers to move to the Panhandle through settlement organizations (such as Oldham County Immigration Association) or immigration conventions held in major cities. Viewed in this light and lacking census data or other pieces of quantifiable data on population growth in the Texas Panhandle, Neal’s assertion that Jarrott was more responsible than any other man in opening up the frontier for the settlement of farmers comes across as a bit of an overstatement.

However, it is a mistake to portray Neal as being anti-rancher in this book as is clear from his dedication to his grandfather Will Neal, a pioneer rancher who settled in Texas. Clearly, Neal’s intention is to highlight the dangers that confronted Jarrott and other homesteader families and not to drag the names of North Texas ranchers through the mud. If readers are looking for an example of Texan courage and grit then they should look no further than Mollie Jarrott or her neighbor Mary Blankenship who rallied the nesters “with gun and Bible on the family alter” to stay put in their homes and not allow Brownfield and his cronies to drive them off the South Plains. In Death on the Lonely Llano Estacado, Neal provides a testament to how the homesteaders overcame great odds to settle in the South Plains of the Llano Estacado, and Texas History enthusiasts would be well-served to add it to their book shelves.

Joseph Fox is the Associate Education Officer at the Museum of South Texas History in Edinburg, Texas. He holds Master's degree in History from Texas State University in San Marcos, Texas. His areas of research include Borderland and Texas Music History. He has written articles for the Handbook of Texas History, a historical marker for the Texas Historical Commission, and completed a Master’s Thesis on the relationship between Lone Star beer and the 1970s Austin music scene.