Two Poets: Part 2

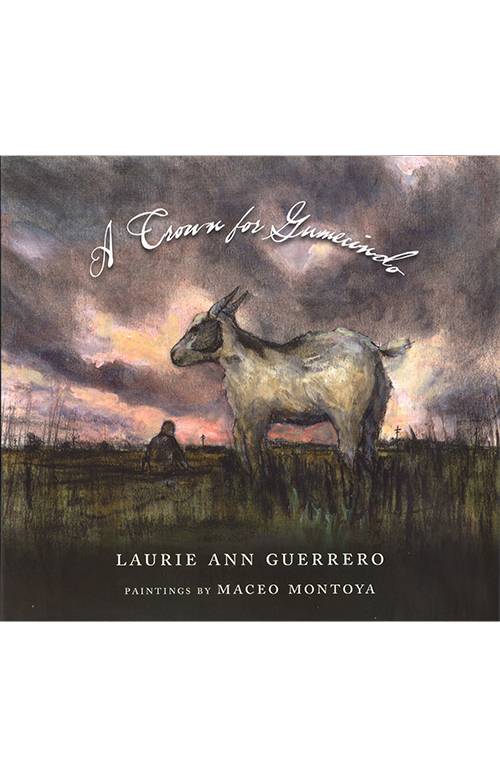

A Crown for Gumecindo

by Laurie Ann Guerrero

San Antonio: Aztlan Libre Press, 2015

90 pp. $24 cloth

Review Essay by

Sarah Cortez

Laurie Ann Guerrero's A Crown for Gumecindo contains the author’s poetry and the paintings of Maceo Montoya as a response to the poems. This book has been conceived and formatted as a memorial to the poet’s grandfather. Fifteen poems are arranged in the manner of a crown sonnet (although, a traditional crown sonnet only contains seven poems) with the poems interlocked by ending and beginning lines, and the final poem containing each previous poem’s beginning line (or its close metrical equivalent). There are additional elements added within the poems in a faded ink that the foreword tells us are from the poet’s “memory, dreamscapes, and conversations.”

Guerrero uses this structure to bring the reader into her private world of grief and mourning. It is a world characterized by haunting, resonant images and surreal actions. Although some of the poems utilize moments of narrative structure, the poet chooses instead to explore the lyrical nature (brief, musical, memorable) of a fourteen-line poem, loosely based on traditional sonnet form. Thus, the reader catches glimpses of a world outside the poet’s reality, but it is the poet’s emotions and willfully narrowed vision that is consistently foregrounded—as must be done to fulfill the task of the lyric poem. Guerrero is effective in accomplishing this in many of the poems.

The most interesting aspect regarding form is how the poet uses some of the elements of the traditional sonnet, but not others. For instance, other than a rhyming final couplet, there is virtually no recognizable rhyming sequence in the poems that lack a clear acoustical relationship between language to strengthen the poems in the absence of such a structure.

At times, the poems sing in the iambs traditionally associated with sonnets. The lines are varied in their use of the five-foot length, mostly accommodating this aspect of a sonnet. There is no doubt that within the past 150 years, the sonnet has become more of a flexible container. Thus, a poet may find examples ranging from the strict adherence to the sonnet’s various forms—forms at which the New Formalists, such as A.E. Stallings, Marilyn Hacker and Marilyn Nelson excel—to playful but conscious transgressions and subversions of the forms.

However, the important question, especially in willful subversion, is does the poem gain in its integrity? Does the poem profit as a whole by the poet’s choices? Has the poet stayed with the material long enough to extract from herself the best that can be obtained or simply taken easier roads that require less effort than a stricter formalism requires? Even Robert Lowell, a mid-career yet masterful practitioner of the sonnet’s intense meditative aspect said his fourteen-line, non-rhyming poems were not sonnets but fourteen-line poems. It is later editors and commentators such as Frank Bidart and Helen Vendler who have called them “sonnets.”

Perhaps in an effort to smooth such risks and subversions, this volume contains a lengthy foreword by author/songwriter Tim Z. Hernandez. The foreword reveals much of Hernandez’s preoccupations and one guesses, by extension, of Guerrero’s. Yet, why does less than 250 lines of poetry require four to five pages of explanation and backstory, historical references, quotes from an interview, and an apparently important epigraph in Spanish (the first lines in the book) with no translation into English? Aren’t the poems themselves strong enough to sweep the reader into the poet’s vision without such protracted preparation? One is tempted to urge the poet: Trust your reader. Trust your reader to hear your song.

In picking up this book, the reader longs to hear from the poet herself immediately, to enter into her world of bold colors and bolder statements—a world where she doesn’t care if the reader understands her, a world she is compelled to shred, then share, then walk away from. A reader closing the pages of both Thomas’s and Guerrero’s books will have the same intrinsic reaction—the wish to read the next book. Vision, voice, and craftsmanship will ensure refreshment and a vitality.

Sarah Cortez is a Councilor of the Texas Institute of Letters and winner of the PEN Texas Literary Award in Poetry. She is an award-winning anthologist and writer with hundreds of publications worldwide. Her latest anthology is Goodbye, Mexico: Poems of Remembrance (Texas Review Press, 2015), already an award-winning book.